| Making cheese | ||

|

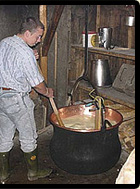

Stirring the cheese

|

The final stage is the maturing process. The cheeses are kept in cellars with humidity of over 90% and carefully controlled temperatures, depending on the type. But there's no question of simply leaving them there and forgetting about them. Storing cheese is a skilled job too. In the cellars, as the natural fermentation continues, they continue to be rubbed with brine and turned. Some cheeses have a special recipe for this daub. Appenzeller, for example, is treated with a mixture of white wine, herbs and spices. The maturing time varies with the type and quality of cheese. For soft cheese it is only a few weeks; for harder ones it is always several months, and may even be years. Even while they are maturing, the cheeses are tested for quality. Inspectors have special probes to withdraw small samples to check taste and general texture, and they tap the cheese with a kind of tuning fork to detect cracks hidden deep beneath the rind. Tête de Moine shaved by the girolleSwitzerland Cheese Presentation counts too It is not only the edible ingredients which make a cheese special. The strip of red pine bark placed round the Vacherin Mont d'Or before it starts maturing is crucial. No other tree will do, and the bark must be taken as soon as possible after felling. This cheese, incidentally, is made only between the end of September and April. When it comes to Tête de Moine, there's only one way to serve it. It must be shaved, not cut into hunks. One theory about how it got its name - "monk's head" - says that the top was always sliced off so that the required amount of cheese could be shaved out, and the effect of replacing the "lid" was to make the cheese look like a tonsured head. Nowadays a special instrument called a "girolle" is used, which shaves the cheese into elegant rosettes. |